Upcoming events

-

KATHERINE MAY, Enchantment — 20th May, 7.30pm

Bone-tired, anxious and overwhelmed, the author of Wintering sought to feel more connected and at ease by exploring the restorative properties of the natural world and reawakening her sense of wonder.

-

ANNA FUNDER, Wifedom — 5th June, 7.30pm

Anna Funder is coming to Backstory! We’re thrilled that the Stasiland author will be joining us in person, all the way from Australia, to talk about her latest book, a biography of Eileen O’Shaughnessy — George Orwell’s wife.

-

REFUGEE TALES in aid of Wandsworth Welcomes Refugees — 19th June, 7.30pm

Iraqi author and activist Haifa Zangana will read the tale she has written for the fourth anthology of Refugee Tales. She will be joined by a person with first-hand experience of immigration detention. The event will be chaired by Arthur Smith, the self-appointed “night mayor of Balham”.

-

Backstory summer sessions — the return of our popular music nights at the bookshop. Book your £5 ticket now to secure your spot:

-

Fiction book club on Zoom, 18th June: Katherine Heiny, Games and Rituals

-

Non-fiction book club on Zoom, 28th May: Daniel Chandler: Free and Equal

WE’RE VERY LUCKY at Backstory that most of our author events sell out. Even so, some hot tickets are hotter than others. We couldn’t believe it when Marina Hyde sold out in a matter of days. That is, until we invited David Nicholls a few months later and had a rush on our hands. The begging emails when those tickets were gone!

But if those tickets were hot, Alice Winn’s were scorching. When she came to Backstory in March to talk about her debut novel In Memoriam, we sold out in 48 minutes.

So I’m delighted to say that she’s coming back! Better still, she is going to interview the author of the debut novel I’m most excited about this year, Yael van der Wouden’s The Safekeep, which is published on 30th May and is our June book of the month.

In the conservative Dutch countryside in the early 1960s, a young woman still tends the family home — keeping rigorous inventories of its contents — years after her mother has died and her siblings have moved out. She is left to keep standards, and her own company. Until, that is, one of her brothers is called away on business and he imposes his new girlfriend on the house.

And so the stage is set for a beguiling, claustrophobic and inventive summer read. Trust me, you’ll be wanting to talk about The Safekeep when you put it down.

And who better to talk it through than Yael, Alice Winn and the Backstory gang? Grab your tickets now.

One of the things I like about the novel is how well Yael writes about sex. Perhaps this is unsurprising given that erotic writing is one of the things she teaches her literature students.

To whet your appetite for the book and the event, I reproduce in full below the lovely article she wrote for the latest edition of our Backstory magazine, all about this topic. You can subscribe to the magazine for as little as £8.91 a year here.

Tom

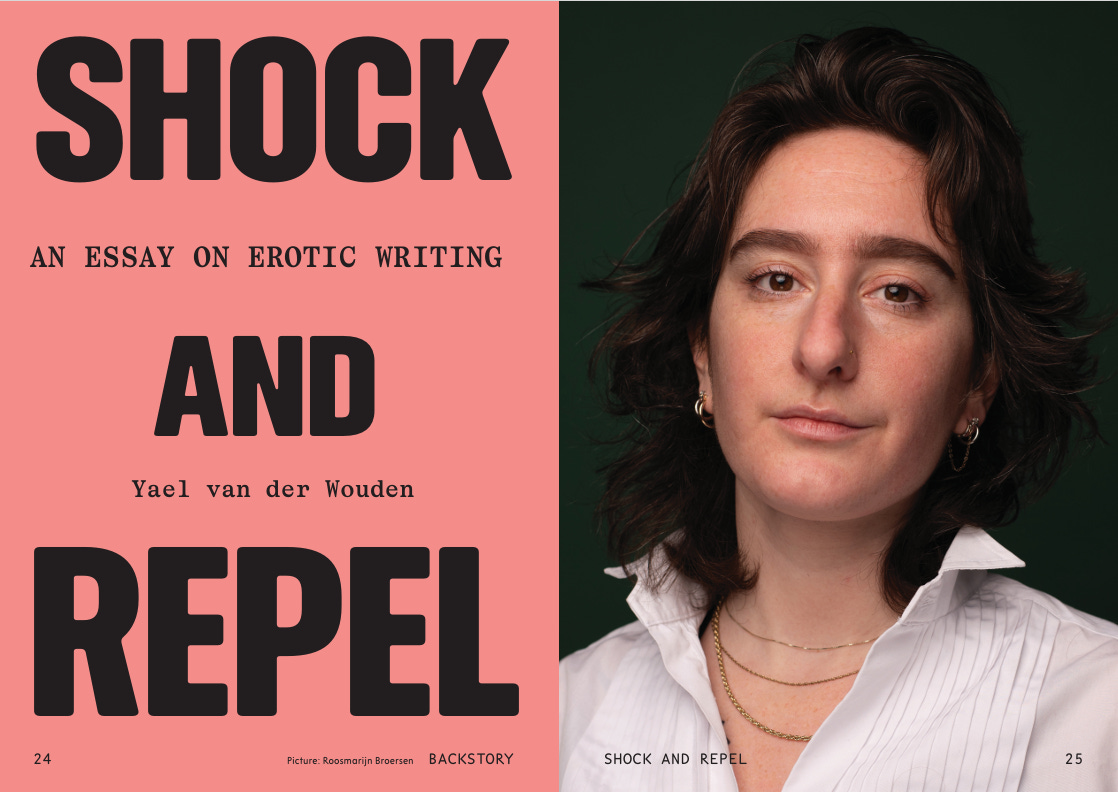

SHOCK AND REPEL An essay on erotic writing by Yael van der Wouden

One time my friend B. got a dirty text from her lover while we and two other friends were out for drinks. It was a balmy summer night, and we were on the bar’s patio – outside under a tree, angel lights on strings, everyone smoking. My friend was in a state about it: in the bellows of her desire for her lover, she could hardly focus on anything that night.

Me and the others were sympathetic and drunk. I myself had been stuck in the mire of a stagnant, one-sided love affair with another close friend who was also present – listening in, posture loose and eyes keen.

I said to B., “Why don’t you just text her back then?”

And B. said, “Oh I wouldn’t know what to text, what would I text? I wouldn’t know what to text.”

And I, brave with alcohol and my own unrequited love sitting so near, said: “I’ll tell you what to text.”

I dictated, she wrote. We were all flushed. It wasn’t very explicit, that text. But it was purposeful, and it was dirty enough. She waited until our other friend went to get us another round of drinks to ask, quiet and intense, “Have you done that before? Texting like that?”

I had and I hadn’t. My first foray into writing anything resembling erotica was at 14. I had watched a TV show, I was obsessed with the TV show; I went to the local library and paid €2.50 an hour to go online where I found a forum of other people also obsessed with said TV show. I wrote a little story about two minor characters making out and posted it.

I hadn’t kissed anyone yet myself, though I’d thought about it a lot. I’d been thinking about it since as early as I knew it was possible – the putting of one’s mouth to someone else, the pressing of bodies together. Mysterious and fascinating and something I couldn’t wait to have for myself, and something I was terrified of just the same. The response on the forum was: “tongues don’t bend that way when you kiss, how old are you?” I replied “20”, and deleted my account.

Miraculously, though, I was not at all deterred. I tried again, and again. And then a friend gave me J. M. Auel’s The Valley of the Horses. There was a phase, around this age, that I can retrace by looking at the spines of the books I read: there’d always be a cracked fold around where a love scene would be. I’d read them and re-read them, desperate for both the thrill and the comfort of it – the safety of experiencing desire only on the page.

By the time I was actually 20 the internet was strewn with my dirty little stories. I’d find a forum, post something, disappear, only to return months later with a new alias and a new story – the point was to do it, but to be untraceable.

Then one time, an online publisher of erotica contacted me through a comment section to tell me: the work was good, and did I want to sign with them? I was terrified. I never answered, though I stared at the message often enough. It was fine, I thought, to do what I did in secret; it was another thing to do it in earnest, to do it with purpose.

I would circle that notion of purpose for a long time. At the end of that one night, after B. had left to be with her lover and me and my sad-love friend were walking home, the silence felt too heavy and meaningful. Then my crush joked and jostled me and laughed and said, “I didn’t know you could talk like that!” I could’ve done something, then. Used those words that were apparently available, make them into action. Be purposeful about them. But I didn’t.

There’s a strange relationship, I’ve always felt, between the erotic on the page and the erotic in life, and what people expect having had the one – then the other. The fantasy versus the reality, the thinking about it versus the doing it. I once spoke to a friend of how I wrote my first sex scene long before I ever had sex myself, and what it was like to have had years of experience in the imaginary, but still be terrified of making it real. She was curious: “was there anything that surprised you once you had sex, anything that you realised you’d written wrong all these years?” My answer was so immediate that I had to take a pause afterwards, and consider whether I meant it, but I did: “No,” I said. “Not at all.”

Sex on the page is not about movements, I’ve found. It isn’t about positions and who does what to whom – it’s about desire. I still believe 14-year-old me could’ve made that make-out scene work, even if tongues don’t bend that way, if I’d known more about building tension, if I’d known more about how to fan desire on the page.

When I teach erotic writing, that’s the crux of my classes, of our conversations: desire. Desire and purpose. It doesn’t matter how much sex you have or haven’t had in your life; eroticism comes from a different set of experiences.

In fact, I’ve noticed that the people who come to class wanting to translate a lived experience to paper tend to struggle the most with making their piece work. They get hung up on physicality, on the who said what, who did what; they forget the reader. They forget that as a writer, you’re not a character seducing another character; you’re not yourself experiencing seduction. You’re a narrative voice seducing the reader.

The first step of teaching erotic writing is teaching how to tap into desire, and how to translate that desire into words. In my classroom we always start at a step removed: non-sexual desire, non-sexual touch, non-sexual sensations. We make lists – things that we want to eat, things that have nice textures, things like good flavours, good smells. The next step is to find the contrast between those good things and the opposite – disgust. Bad sensations, bad textures.

We write sentences where the two are brought together to describe something. An example: warm, leaking yolks. What we’re looking for is a balanced contrast, the sweet spot between that which attracts and that which shocks, that repels. We sit with the discomfort. Then we lean into it. We get purposeful with it.

The way I see it, that’s where you find the overlap between the erotic on the page and in real life: purpose. Doing something intentionally, earnestly, doing something a little filthy and fully embarrassing with intention is where the erotic dwells – that hot tension between humiliation and want.

My favourite part of teaching is when my students realise that it’s not the more literal sex scenes that make them blush, but rather the earnestness of an erotic text. Take, for example, Ellen Bass’s Basket of Figs: “That hard nugget of pain, I would suck it,/ cradling it on my tongue like the slick/ seed of pomegranate.” Or Carol Ann Duffy’s Warming Her Pearls: “I dream about her/ in my attic bed; picture her dancing/ with tall men, puzzled by my faint, persistent scent/ beneath her French perfume, her milky stones.”

These poems are far from explicit – not a single tit, not an ass in sight. And yet, it’s never happened that I’ve read these poems aloud in a classroom without a collective blush rising up from the audience. Once, memorably, after the final line, a student whispered a breathless “Jesus”.

Erotic writing – be it a text to your lover, a letter across seas, a novel or a poem – is, I believe, accessible to anyone who’s ever desired anything, anyone who’s ever yearned or wept for want. The key is to be shameless about it. To understand the accompanying embarrassment as the engine that makes it tick; to understand that purpose is what turns it on.

Extracted from issue 2 of Backstory magazine. Subscribe here for as little as £8.91 a year